Zimbabwe - Customary law – Preconditions

PRECONDITIONS

Customary norms and practices

Zimbabwe

BACKGROUND

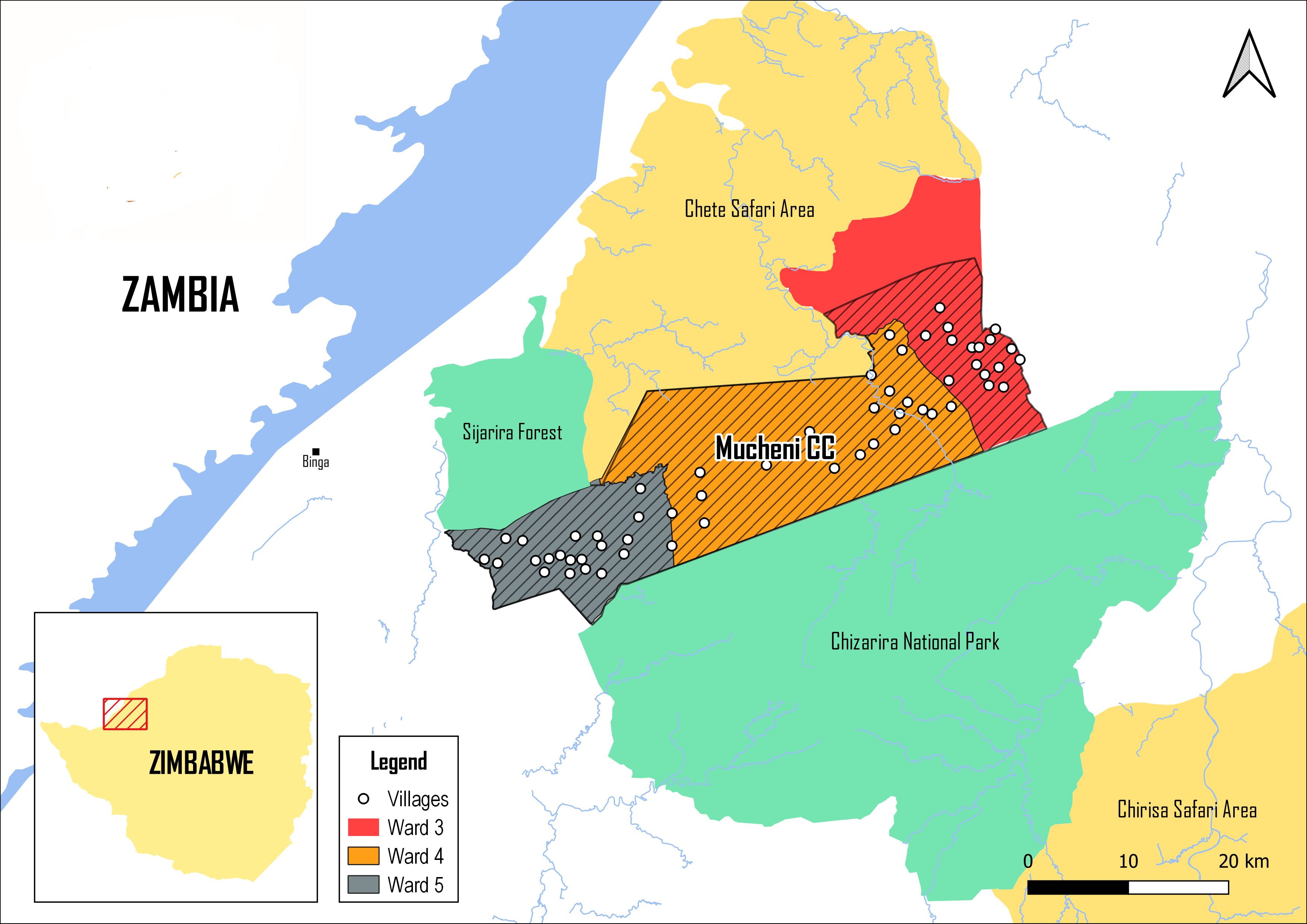

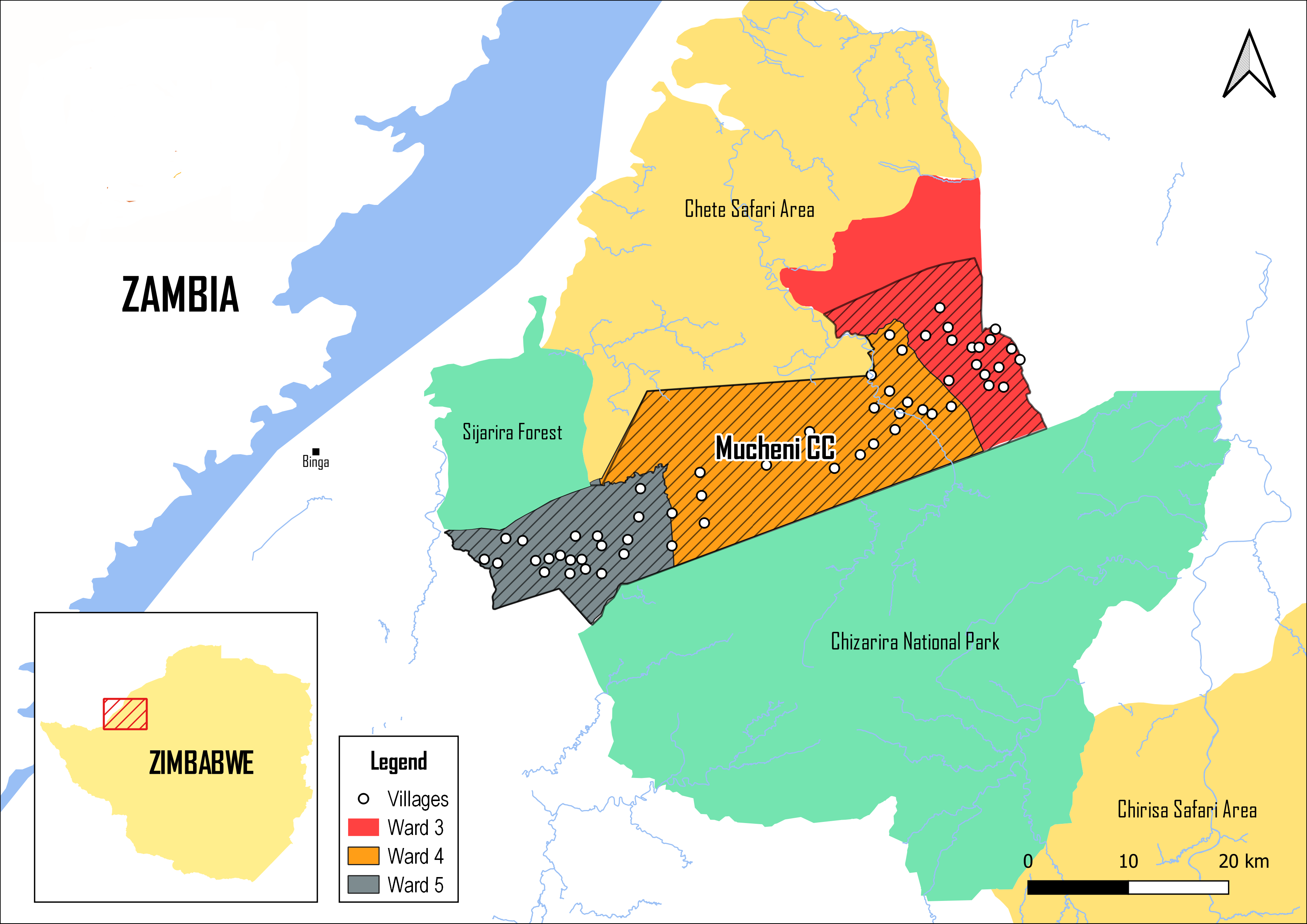

Binga District, situated in the Zambezi Valley, is mainly inhabited by the Tonga and Ndebele. The Tonga are the majority inhabitants of the area and regard the Ndebele as newcomers. Tonga people identify strongly with the Zambezi River, this being the centre of their economic, social, religious, cultural and environmental livelihoods.

In the pre-colonial period, until 1888, the Tonga were a stateless society, known for having no paramount chief and historically were a matrilineal society.

The colonial administration by introducing chiefs and headmen disrupted Tonga's age-old egalitarianism and led to the solidification of fixed boundaries across and between villages as well as the introduction of new ways of dealing with criminal cases that were centred around the chief’s court.

The construction of the Kariba Dam along the Zambezi River, with the related forced relocation in land of small size and poor quality, significantly impacted the lives and livelihoods of the Tonga who were directly and heavily reliant upon the Zambezi River landscape. Indeed, the colonial government established fishing camps far away from resettlement areas, and only men were allowed at these fishing camps. At the same time traditional and cultural wildlife management systems were abrogated and criminalized by introducing the need of hunting permits.

Even with political independence in 1980 the Tonga continued being marginalized, without rights to manage and benefit from wildlife resources in the safaris and national game parks abutting their new villages. The attempt to extend these rights to the local communities by granting the right to use wildlife in communal areas to Rural District Councils (RDCs), has in fact led to tensions between communities and RDCs on revenue-sharing arrangements.

The 2013 Constitution expressly recognizes customary law and customary institutions. It recognizes the role of traditional leaders in resolving disputes among people in their communities in accordance with customary law. It also establishes a dual court structure, recognizing customary law courts whose jurisdiction consists primarily in the application of customary law.

Besides the Constitution, there are several statutes which recognize customary law. These include the Customary Law and Local Courts Act (CLLCA), the Traditional Leaders Act, the Communal Land Act, and the Environmental Management (Access to Genetic Resources and Indigenous Genetic Resource-based Knowledge) Regulations, 2009. All law, customary and statutory , is subject to compliance with the Constitution of Zimbabwe. Any law inconsistent with it is invalid to the extent of the inconsistency.

According to the CLLCA, customary law is still applied in civil matters where the parties have agreed. Local courts are presided over by chiefs and have jurisdiction over any civil case in which customary law is applicable. However, their jurisdiction is excluded, among others, where the claim is not determinable by customary law; or where the claim or the value of any article claimed exceeds a certain amount; or also to determine rights in respect of land or other immovable property.

The Traditional Leaders Act governs the structure of traditional leadership and its duties, which include the resolution of disputes and management of natural resources. Furthermore, traditional leaders have to be consulted in the allocation of communal land under the Communal Land Act. However, customary law’s application is not always recognized in sectoral legislation, particularly in the management of wildlife. Indeed, while the Environmental Management (Access to Genetic Resources and Indigenous Genetic Resource-based Knowledge) Regulations, 2009, provide for community rights over genetic resources, including animal genetic material, the Parks and Wildlife Act (PWA) does not expressly mention any form of customary hunting that traditionally occurred for both subsistence and cultural purposes.

PRECONDITIONS

Customary practices for land use planning

Historically, within Tonga society, the Ulanyika was vested with the responsibility of administering the land in the interest of the community in every neighbourhood: land holdings were allocated for free to individual families as a right to use, and security of tenure was therefore guaranteed as long as the family used the land. The matrilineal arrangements of the past are no longer respected in transferring property. Access and administration of land is no longer the preserve of the Ulanyika or chiefs. The administration of communal land is now under the Rural District Councils (RDCs). The RDCs allocate communal land for agricultural or residential purposes, having regard to customary law and in consultation and cooperation with the chief appointed to preside over the community concerned.

Regarding the administration of land, the chiefs’ role has essentially been reduced to implementing statutory law. The Communal Land Act and the Traditional Leaders Act confer land administration powers on the RDCs, the chiefs’ role being to ensure that the land and natural resources are used within the framework defined by law. Likewise, the headmen’s statutory duties are to mediate in local disputes and to perform customary rites, but only to the extent that such matters are not subject to the general law. Finally, village heads are mandated to consider, in accordance with the customs and traditions of their respective communities, requests for settlement by new settlers in village and, after consulting with the village assembly, make recommendations on the matter to the ward assembly. They can also settle disputes involving customary law and traditions, including matters relating to residential, grazing and agricultural land boundaries to the extent that these matters are not subject to the general law. However, social and cultural values and traditional knowledge systems still persist and continue to play important roles in many communities such as the proposed Mucheni Community Conservancy. Generally, where traditional beliefs are held, sanctions and complementary customary monitoring and enforcement regimes exist. Responsibility for ensuring compliance with local rules in general still remains with the chief.